In early 2022, one of the three major infant formula producers in the United States stopped production at a plant because of possible bacterial contamination that may have caused several infant deaths. Compounded with the ongoing global supply chain crisis, the shutdown caused a severe shortage of infant formula. By late spring out-of-stock rates had risen to 74%.

Only a quarter of infants are breastfed exclusively after six months according to the CDC, leaving the majority of families with babies under a year-old depending on formula.

“When you compare milk banking to other critical donations like blood and organs, this is just in the shadows – it’s not very well known.”

As families struggle with the shortage, interest in donated human breast milk has increased. We sat down with UNC Greensboro expert, School of Health and Human Sciences faculty member Dr. Maryanne Perrin to learn more about donor milk and human milk banking.

“When you compare milk banking to other critical donations like blood and organs, this is just in the shadows – it’s not very well known,” she says. “But it’s been around for a very long time. The first U.S. milk bank was in the early 1900s – it was actually a boat in the Boston harbor serving as a floating children’s hospital.”

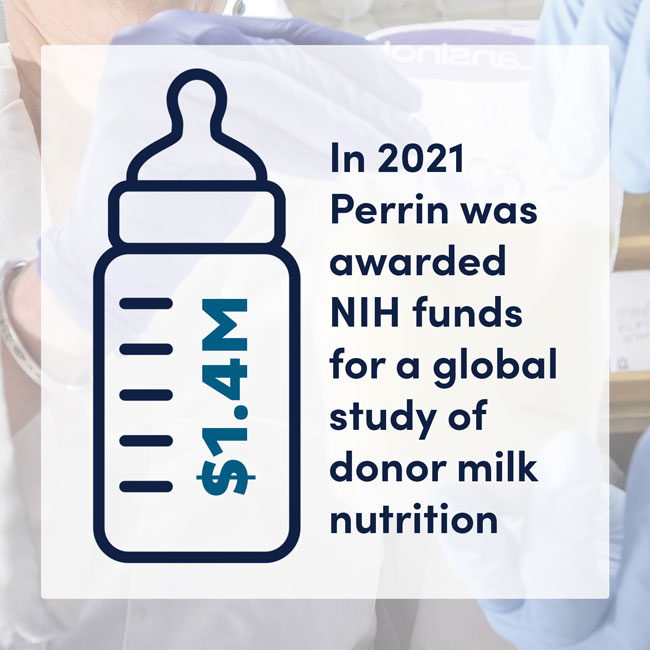

Dr. Perrin has conducted over a decade of research on human breast milk composition, storage, and processing techniques, and she served four years on the board of directors for the Human Milk Banking Association of North America. Her credentials include a doctorate in nutrition, an industrial engineering degree, and an MBA.

What is human milk banking?

Milk banks are nonprofits that collect donations from nursing mothers who are producing more breast milk than their babies need. They screen, process, pasteurize, store, and distribute the donor milk, primarily for the care of premature infants.

“Right now, milk banking in the United States mostly serves hospital NICUs (Newborn Intensive Care Units).

“Sometimes a parent may not make enough milk to meet their baby’s needs. When this happens, parents can usually supplement with formula.

“But for preterm infants weighing less than 1500 grams, or 3.3 pounds, exposure to the cow milk proteins in formula increases the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, or NEC, which is basically death of tissue in the GI tract that can lead to infant death. More than 90% of U.S. NICUs now use donor milk to reduce the risk of NEC.

“Milk banks do a couple of things. They screen donors and their infants and freeze donations. Then, donations are defrosted, pooled, bottled, and pasteurized for distribution.”

Are milk banks safe?

Yes.

“When donors are screened, not only do they screen the parent for diseases like HIV and hepatitis, but they also ask for pediatrician notes to ensure the infant is healthy and growing appropriately. They don’t want donations to divert milk away from an infant that needs it.

“Milk banks operate like a food manufacturer and are governed by FDA regulation. And then the Human Milk Banking Association of North America (HMBANA) provides additional guidelines to keep donor milk safe and conducts yearly audits of the milk banks they accredit.

“HMBANA originally focused on keeping pathogens out. But now they are beginning to focus on the nutrient profile. That’s where a lot of my research is. Milk banking processes can actually influence the nutritional profile of donor milk.

“We just published a paper last year in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition showing that milk banks can retain more nutrients in donor milk if they use different strategies to thaw frozen donations.

“Also, because some nutrients are highly, highly variable in breast milk, we’ve found that pooling milk from four or more donors can create a more consistent nutrient profile in donor milk. In January, we published a study about this in the Journal of Pediatrics – milk from a single donor could have up to 13 times more sodium than milk from another donor. But if you pool four or more donors, the difference between pooled donor milk samples only goes up to 2.4 times more sodium. After that, HMBANA informally sent out guidance to start pooling three or more donors.”

How do I get donor milk?

You’ll need a prescription. And to prepare for high costs.

“We are starting to see donor milk used outside of the NICU. When newborns need supplements for their parent’s breast milk, more and more parents are requesting human milk as an alternative to formula.

“However, most donor milk is still accessed through a hospital setting, and if you get it for the home setting, you need a doctor’s prescription.

“This is where we see some inequities arising. Most of the time donor milk outside of the hospital is not covered by insurance, so it’s expensive.

“One of my colleagues has also documented potential bias when health care providers talk to families about in-hospital supplementation options – she found that parents who were non-White, non-English-speaking, or uninsured, were less likely to use donor milk.

“We are seeing blockbuster growth in milk banking. The number of NICUs using donor milk went from 50% to 90% in just the last five years. Between 2020 and 2021, HMBANA announced a 22% increase in donor milk distribution. More lactating parents are becoming aware of milk banking and donating.

“When I spoke to Lindsay Groff, the executive director of HMBANA, she said this year’s infant formula shortage has led to a roughly 20% higher demand for donor milk so far, though this varies from bank to bank. Many banks have also experienced an uptick in new donors as people in our communities have learned about the formula shortage and want to help.”

“For now, donor milk is not in high enough supply to be a common alternative for formula in healthy and older infants, and the cost is prohibitive. But there are other revolutions in infant feeding happening, including methods to make formula that is more like human milk and technologies to produce human milk from mammary cells.

“In the meantime, when it comes to formula, an important thing to remember during this shortage is not to fixate on getting a particular brand. Companies give away free formula in the hospital and try to get families to feel really attached to their formula brand. But what many people don’t know is that all formulas are governed by the Infant Formula Act. All manufacturers have to meet a minimal nutritional profile – a profile so much tighter than human milk.”

What’s better – formula or donor milk?

It’s complicated.

“It’s not a slam dunk for donor milk. We know a parent’s milk is the best nutrition for their child – but donor milk is not the same thing as a parent’s milk, due to a multitude of factors.

“If you’re a preterm infant in the NICU, donor milk is better, because it prevents NEC. If you’re a term infant, donor milk may not have appropriate nutrients because of the losses that occur during pasteurization.

“We just don’t don’t have enough evidence about the effects of donor-milk feeding in populations other than preterm infants.

“So far, a very small study has shown that full-term infants experience less GI distress on donor milk, and donor milk actually improves low blood sugar better than a parent’s milk.

“But infants in the NICU don’t grow as well on donor milk compared to infants receiving their parent’s milk or formula, and this might also be the case if donor milk were used when infants go home.

“My hypothesis is that donor milk requires a specialized fortifier. We found that less than 1% of 300 samples we got from U.S. milk banks achieved the sodium targets that current fortifiers are supposed to help them achieve.

“It’s still an open question if donor milk could promote better infant growth if the nutrient profile in donor milk was more standardized and a fortifier was developed specifically for donor milk. My new NIH-funded research explores some of these questions.”

Interested in donating? There are 31 HMBANA-accredited milk banks.

Story and interview by Sangeetha Shivaji, Research and Engagement,

Susan Kirby-Smith, University Communications

Photography by Martin W. Kane, University Communications