Dr. Heather Brook Adams in UNC Greensboro’s Department of English has just published a book that reveals a dark time in reproductive history in the United States.

“Enduring Shame: A Recent History of Unwed Pregnancy and Righteous Reproduction” (South Carolina Press) is sure to make a splash on publisher lists and in university classrooms as other professors adopt the book for their health rhetoric and gender-related courses.

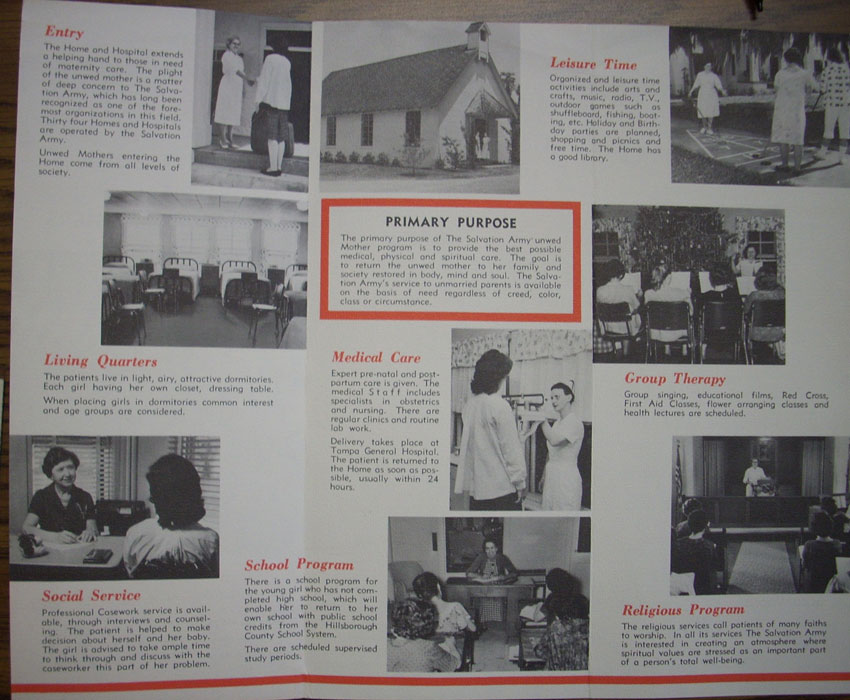

The book shares the history and personal stories of unmarried women in the 1960s and 1970s who became pregnant and were taken to live in secrecy in maternity homes before giving birth and relinquishing their children. Adams examines reproductive justice in a myriad of ways concerning body autonomy, the right to parent and be with one’s children – or not, histories of forced sterilization, medical and social practices that shifted over time, and the role of shame and blame in shaping discussions of reproduction and well-being. Dr. Adams is also currently co-editing a collection with Dr. Nancy Myers on rhetorics of reproduction. She is a cross-appointed faculty member in UNCG’s Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program.

Could you describe the book for us?

I think there are a lot of important stories that I’ve tried to share and amplify while also making an argument about the role of shame in relation to reproduction. I don’t think this book reads like other academic books. It might have some things that are unexpected to people – like the personal stories and memories. The scope of the book is the 1960s and the 1970s. The conclusion engages with contemporary questions about reproductive sovereignty and the recent history of public feelings and morality. That brings us to this moment and the news we’re dealing with now, in relation to Roe v. Wade.

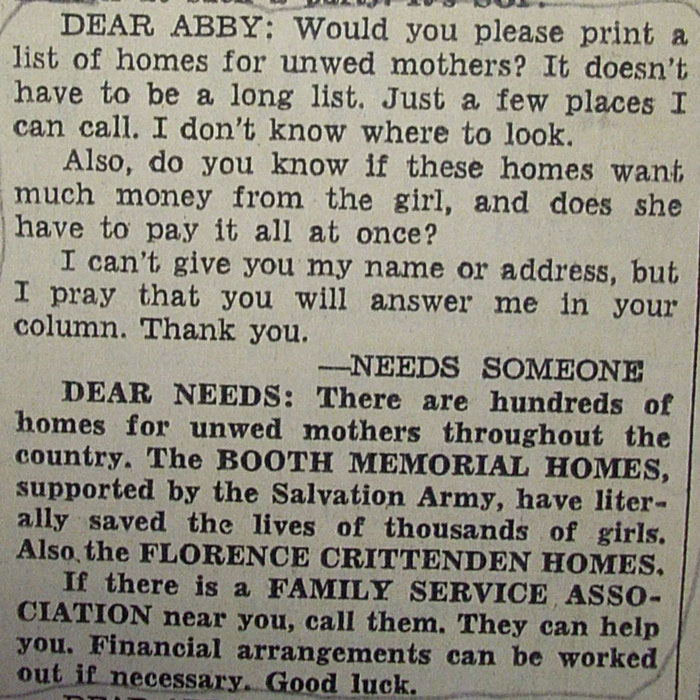

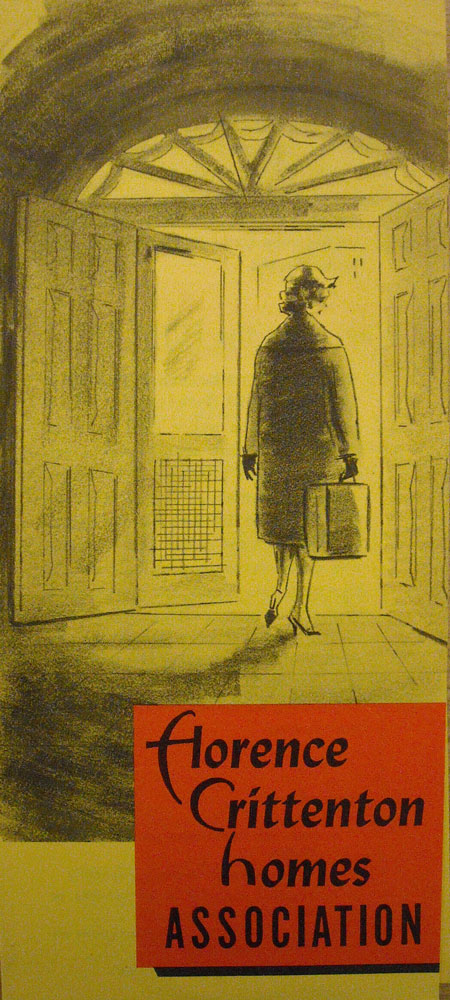

One of the first chapters of the book really goes back to the 1960s, primarily, and draws from my interviews with women who were unmarried and pregnant at that time. These were mostly white women who were forced to hide their pregnancies and really hide their identities as mothers as they relinquished their children for adoption. They are harrowing stories, and when I first learned about this practice some years ago, it made me ask: What kind of strange history is this? So, I listened to these women’s stories, because there isn’t a whole lot published about them, even though the practice was common in many communities, especially white communities. I wanted to understand what happened to these women in the process of going away. So, that early chapter of the book presents the women’s experiences based on their first-hand accounts. The mothers were so generous in sharing their stories with me, allowing me to hear how central shame was to their experience, how related shame was to their experience of giving birth and to an identity that they had to erase, which is really tragic.

The rest of the book moves through different moments of the 1970s, where things are seemingly more progressive because public interventions are put in place. Of course, Roe is one of those protections, and I look at public writing that suggests that shame has disappeared based on these policies and shifting practices starting to take hold. Of course, there is a much deeper story of how shame endures even as it shifts and moves.

I also look at texts ranging from journalism to court documents, and legislation such as Title IX. We think of Title IX today as really important legislation that relates to sports as well as sexual violence or sexual assault on campus. Originally, it also prevented young people who were suspected to be pregnant from being kicked out of public high school, for example, which had happened so frequently in earlier decades.

Overall, the book allows me to consider how shame is operationalized publicly. Even for those who experience shame, the way it actually works can remain somewhat mysterious. Many women I interviewed said, “Why didn’t I have any other option but to leave my home and go undercover for four months, and not know what was going to happen to me or to the baby?” A mother I interviewed recently wrote to me to say that she is giving some of my work to her son, with whom she has since been in reunion. That child struggles to understand why his mother gave him up for adoption, so the idea is that the book can help untangle and explain how shame and secrets were – and are – so powerful. Shaming is something I explore in the book, because it’s this way of casting out these marked women as a way of purifying others. It is an act of rhetorically constructing belonging and righteousness.

What’s surprising about reproductive history in this country and the conversations around it?

So, in looking at these moments in the 70s and these pieces of public discourse, there’s a story out there of how things got better, because shame went away. But my finding is that shame is still lurking throughout this decade. And if we don’t step back to admit that we don’t understand a deeper story around reproduction and the precarity of what we think of as assurances – or protections or fundamental rights that are never going to be challenged – then we’re really missing the deeper story. And we’re, we’re probably going to continue to have surprises. I think there’s a lot we can learn from just a few generations back about the fickleness of change, and some of the things that feel like they could never change, but they do.

The entry point for reproduction and reproductive rights and abortion rights in the United States has mostly been understood through a white middle class, feminist orientation. And there have been many people, people of color especially, who have had a much bigger picture of all the complex ways that people can exist in relation to reproduction and making good, informed decisions for not only themselves but for themselves in their community – kinship communities and their spiritual communities. This is complex stuff, and it gets to the heart of some of the most important decisions we make in our lives. Thought leaders have long developed ideas around reproductive justice, which is a bigger story, a bigger approach, and a more inclusive approach than “pro-choice / pro-life.”

That dichotomy makes for good headlines, because it’s really simple and it puts us in one of two camps. But I think that that framing has failed so many people, and it doesn’t allow reproducing people and people who care about reproducing people to get into the gritty complexity of things related to reproductive health, having a child, or not having a child – all of this.

Where can we go from here in our understanding?

There’s a lot of good work that has been done. The larger picture of reproductive justice is less about arguments around privacy and is much more of a human rights-based approach, thinking holistically about the people involved in these issues and complexities. Storytelling as a methodology of reproductive justice helps – really listening to each other and, and grappling with big and differential things that don’t hit the same way in different people and different bodies, different communities. Thinking about reproductive justice in larger ways is new for lots of people, who may be stuck in a “pro-life vs. pro-choice” mindset.

It’s a very powerful idea that if you are living in a body that can reproduce. you’re always socially cast as in a pre-pregnancy state, where you need to be managing the risk of pregnancy. So, we can think about it in terms of sex education, and abstinence, and all of the gendered ways that that gets taken up. There’s an unequal weight of responsibility, and weight of potential risk that falls on people who can reproduce, versus the shared responsibility, the knowledge of how our bodies work, the normalization of different orientations to like, sexual health and well-being.

One of the curious things is that the maternity homes, as the women described them to me, were often prominent, old, haunting Victorian buildings. So, they were sites of invisibility, but as structures, they were highly visible. Young white women who were held solely responsible for an unrighteous pregnancy might have gone to one of the homes to hide in anonymity, but the open secret of the homes functioned as a sort of public good – a reminder of who the so-called “bad girls” and “good girls” were. The shame that I trace in the book relates to a fear – that when girls didn’t have to hide, there would be less control, less ability to create and perpetuate binary categories. There’s a curious relationship between visibility and invisibility and our sense of the threats and risks related to that. We can bring this insight into how we think about a lot of ongoing issues that affect young people.

Could you describe your teaching experiences and work with students that may relate to the subjects touched on in the book?

I teach an advocacy class in the English department – “Public Advocacy and Argument,” which is part of our department’s minor in Rhetoric and Public Advocacy. My training as a rhetorical scholar takes very seriously that there are many ways to look at an issue. I always tell students, “I am not here to persuade you to believe one ideology. I am here to help us think and to help us rhetorically listen and to learn together.” That class provides students with a framework for practicing advanced critical thinking and writing and exploring possibilities as advocates in relation to something that we care about.

I also developed a course called “Health and Wellness and Cultural Context.” The idea is that, typically, we tend to think about things related to health, wellness, our bodies, in pretty non-rhetorical ways – like, if we have a fitness app or tracker, we can reliably measure the health of our body. Or, when we go to the doctor there’s a sense that there’s an expert who’s going to reliably give you the information and care you need. And these are seemingly objective ways of being in relationships with our bodies, when we think under the large banner of health and wellness. The course asks how we’re persuaded to think certain things about our bodies, how we’re persuaded to pay attention to some aspects of our physical experience while ignoring others, how there’s knowledge about some aspects of health and wellness and a lot of bad information or lack of knowledge in relation to those living in marginalized bodies and in women’s experiences with their bodies. Their experiences with reproduction or their own mental health, for example, are called into question or dismissed altogether. There’s the fascinating history of “hysteria” that we explore in this class. What is hysteria? What has hysteria meant in the past? And how is it a junk diagnosis? And how does the specter of hysteria still linger today for people experiencing, for example, what is often and popularly called “chronic fatigue syndrome”? And how do these experiences relate to gender to race? This is just one example of what we discuss in the class in thinking rhetorically about health and wellness – we’re always asking who gets to speak, who listens, who is believed, etc.

It’s important for students to learn that history, and also feel empowered to explore their relationships to their health and care about their wellness. The goal here is not to sow distrust in science or just to question authority, but to learn critical literacies related to health as something that we think about differently across communities and across time – and to identify and practice ways for care-seekers and care-providers to more fully listen to each other, especially when emotions like fear and shame take hold.

We have feelings about our bodies, and we have feelings about a lot of these big topics that are very personal, and also very public. How do you sort through all of that? How do you advocate for yourself and those you love? How do you recognize patterns of people being dismissed or not believed in relation to very real and important things that they’re experiencing – chronic health issues, reproductive emergencies, things like that? I teach a similar course at the graduate level also, and all the students have been really receptive to it.

I’m always committed to having students do projects in my classes that are meaningful to them. So, we learn a lot through collective sharing and self-directed inquiry. I encourage students to apply the course’s queries and these insights to something they really care about. That’s gratifying to see, and the students respond well to that.

Dr. Adams not only works with English majors and students in the College Arts and Sciences, but she also teaches School of Health and Human Sciences (HHS) students in her “Health Rhetorics” course. She is part of a team of professors and students who participate in the North Carolina Survivors’ Union who are researching the power of story sharing and listening toward structural change. She and several other scholars from UNCG received a UNCG Pathways and Partnerships grant to research avenues for navigating the complexities around stigma, shame, and harm reduction measures for pregnant and parenting people who have used drugs.

“Among those in the harm reduction community, there are many stories of family separation, of losing a child – it’s eerie how similar the stories sound to those of the women I interviewed for my book, even though the context for that loss is in many ways very different,” she says. “ I’m new to the team, and I’m learning so much from those who have been doing this work for a while. There are no easy answers, but there is certainly a lot of work to do.”

For students interested in these issues, there are also many other experts and courses at UNCG that focus on reproductive justice and health in relation to gender. History professor Dr. Lisa Levenstein, who directs WGSS, teaches courses on U.S. women’s history and reproductive politics, and a chapter of her recent book, “They Didn’t See Us Coming,” explores the founding of SisterSong, a central player in the contemporary reproductive justice movement.

In HHS, Paige Hall Smith and other instructors teach graduate and undergraduate sections of a course called “Gender and Health.” This past spring, UNCG’s Public Health Education program hosted the “Voices for Reproductive Justice” conference, orchestrated by faculty Christina Yongue, MPH, Dr. Amanda Tanner, Dr. Erica Payton, Dr. Meredith Gringle, Dr. Tracy Nichols, and students Elondara Harr, MPH, Sulianie Mertus, MPH, and Nia Washington.

Learn more about WGSS

Students can earn a bachelor’s or master’s degree in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies or pursue an interdisciplinary post-bacculaureate certificate

Interview by Susan Kirby-Smith, University Communications

Images courtesy of Heather Brook Adams